MSPIFF43: Occultist Revenge, Satirical Body Horror, Feminist Archives, Absurdist Dystopia, and Surreal Duration [Dispatch #2]

Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell

by Maggie Hennefeld (University of Minnesota)

April was a month of bountiful cinematic offerings in the Twin Cities. L.A. Rebellion filmmaker Zeinabu Irene Davis visited the Walker Cinema to present a rare 16mm screening of her masterpiece Compensation (1999), which is finally being restored by Janus/Criterion and will have a theatrical release this fall 25 years after its festival premieres in Atlanta and Toronto in 1999. Mizna launched its new “Insurgent Transmissions” series with a packed screening of Annemarie Jacir’s humorously heartwarming Palestinian road movie, Wajib (2017), in the glorious Bryant Lake Bowl Theater. Alfred Hitchcock and Arnold Schwarzenegger vied for repertory eyeballs at the Trylon Cinema. Last but not least, the 43rd Annual Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival! This year’s line-up included over 200 screenings—not to mention industry panels, director interviews, special events, and galas galore. I personally struggle to clear my end-of-semester schedule for those 2 weeks every April, when I would love nothing more than to dive headfirst into the treasures of MSPIFF! This year, I managed to attend 5 screenings. Here are my brief thoughts—with thanks to Nazeeh Alghazawneh for inviting me to share.

Copa 71 (2023) — James Erskine, Rachel Ramsay

The only documentary feature I managed to catch in the festival—which boasted regional premieres of new docs such as Porcelain War, Sugarcane, and Daughters, along with biopics on Luther Vandross, Anita Pallenberg, and John Galliano—this one felt especially timely. A conventional talking-head exposé, Copa 71 seamlessly interweaves extensive archival footage of the 1971 Women’s Soccer World Cup, whose explosive international popularity provoked FIFA to suppress women’s participation in the sport and censor public memory of these events in Mexico City and Guadalajara from the history of women’s professional athletics. Co-produced by Venus and Serena Williams, Copa 71 sets the record straight.

Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World [Nu astepta prea mult de la sfârsitul lumii] (2023) — Radu Jude

I enjoyed this film as much as I felt profoundly irritated by it. Romanian rabble-rouser Radu Jude’s provocauteurism is often a self-congratulatory Godard quote (or Méliès wink) away from overshadowing the substance of his film’s satirical critique, which is otherwise on point. To paraphrase the film’s thesis, nothing is real and the material consequences are brutal. Media surfaces—from green screens to TikTok filters to Zoom virtual backgrounds—add an absurdist edge to the freewheeling pastiche whereby workers are homicidally exploited, violent misogyny runs rampant, and corporate elites commit ritual cannibalism as a staple of their plant-based diet.

Evil Does Not Exist [Aku wa sonzai shinai] (2023) — Ryûsuke Hamaguchi

I’ve been a big fan of Hamaguchi’s fluid cinematography and slow-burn character studies since marathoning his 5+ hour opus (perversely titled) Happy Hour (2015) during the long months of pandemic lockdown. His films encourage a patient gaze—allegory escalates across episodic encounters in ordinary spaces of isolation and movement: on the bus, in a corporate cubicle, driving a car, or protesting a “glamping” development. Despite its slightly shorter running time than The Sound of Waves (2012) or Drive My Car (2021), Evil Does Not Exist delights in the utter beauty of evocative tedium in a world addicted to relentless novelty, extraction, and spectacle. The film’s tantalizing title “evil does not exist”—an alleged Albert Einstein quote with Arendtian vibes—recalls Freud’s definition of negation: no means yes, at least in the analytic context of unconscious repression. In other words, evil does not exist. Then again, maybe it’s the absent spectator who does not, as we project ourselves into ambiguous fantasy worlds while the planet implodes on the altar of new “glamping” developments.

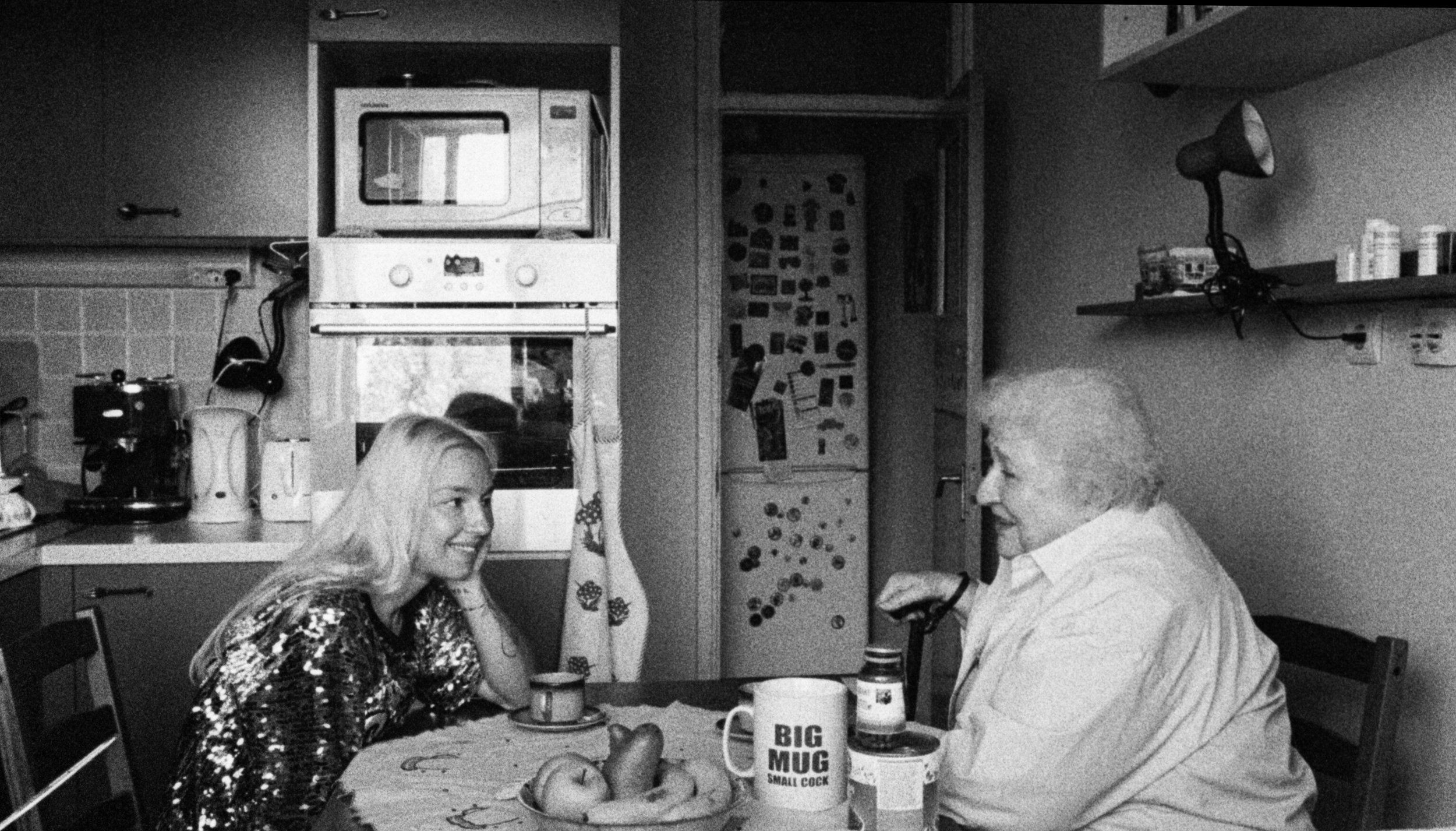

Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell [Bên trong vo kén vàng] (2023) — Thien An Pham

“Slow cinema” at its most resplendent. A road movie about ghosts—present and absent—this film has a visceral texture that you learn to inhabit over the course of several hours, from the sensation of a cellphone vibrating in a massage parlor to a jerky motorbike tracking shot and through a series of surreal fantasies and vivid nightmares. I am still jostling some of the film’s images out of my body.

Working Class Goes to Hell [PRadnicka klasa ide u pakao] (2023) — Mladen Djordjevic

Keeping apace with my appetite for class revenge body horror, it was a no-brainer to stay out after my friend’s 39th birthday party for a late-night screening of this diabolical satire. Crudely summarized, the Balkan proletariat embraces the paganist occult after a factory fire leaves them destitute and bereaved. Radu Jude’s revisionist take on the Lumière Brothers’ early actuality footage of Workers Leaving the Factory (1895) in Do Not Expect Too Much… called this film again to mind. Where else do workers go after leaving the factory, if not inevitably back to hell? Except Đorđević’s version of hell is a feast for the bodily lower stratum! The bloody climax feels well earned: the oppressed people rise up and demand carnal liberation from their political wounds, festering emotions, and violated libidos. Though inconsistently weird and unevenly paced, there was nowhere else I’d rather be at midnight on a Saturday.

*An afterthought on methodology

Of the 200+ films in the festival, why did I choose these five, and how might their totality offer us a snapshot of this current moment in international arthouse cinema? Class revenge, apocalyptic satire, absurdist malaise (of somehow continuing on despite living after “the end”...), and slow-burn durational possibility are a few of the core themes that have struck me and stayed with me in retrospect. When can cinema open up gateways onto alternative realms and unrealized historical potentials—as genocides unfold with impunity, protests rage on college campuses across the US, the planet floods and burns, and class immiseration fuels the flame of resurgent authoritarianism? What (if anything) does cinema have to say in response? According to my (albeit fragmented) experience of MSPIFF, moving images still provide vital lifelines for a re-enchantment of the broken present: uncovering lost archives, releasing suppressed sensations, or simply remembering when, at last, it is time to say enough is ENOUGH!!!

about the contributors ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭

Maggie Hennefeld is Professor of Cultural Studies and Comparative Literature at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. She is the author of Death by Laughter: Female Hysteria and Early Cinema (Columbia UP, 2024) and Specters of Slapstick and Silent Film Comediennes (Columbia UP, 2018). She is a curator of the 4-disc DVD/Blu-ray collection Cinema's First Nasty Women (Kino Lorber, 2022) and co-director of Archives on Screen, Twin Cities.

MSPIFF43: awtt.haaus & friends — DISPATCH #1

The Beast [La bête] (2023) — Bertrand Bonello

By Dave Gomshay

Big fail, but not for lack of trying and honestly I'm still pretty giddy over how cannonball wacko it is. Once again, Lea Seydoux elevates anything she's in, just unreal charisma and magnetism. George MacKay acquits himself admirably, continuing his career ascent. Credit due for everyone daring to make something different. First half got to be a drag, then after the shift into the second half, things at least got interestingly bad. Big swings. Might even be the kind of movie that I come around to someday, but I'm going to let it be for a good while. I'd like to see an Olivier Assayas version.

By Natalie Marlin

Nothing like a cold open where Léa Seydoux acts out a horror scene in front of a green screen before getting abruptly datamoshed into oil painting smears to knock a fest audience expecting a straightforward Henry James adaptation into disarray. Bonello's genre-anarchic sensibilities have never been more heightened, blednding everything from near-future climate dystopias to an extended probe into the nature of Elliot Rodger types—not to mention touchpoints ranging from Cloud Atlas to Twin Peaks: The Return to certain works of Harmony Korine—into a uniquely haunting depiction of the baseline anxieties that make up human existence as we know it, and our visceral impulses to attack our responses to these anxieties rather than their root causes. The compounding discomfort of all these jolts is enough to even forgive the film's deceivingly dry first half-hour, one that I imagine plays better on a second viewing, with an awareness of just how insidiously it feeds into Bonello's narrative of repression and human erosion.

by Nazeeh Alghazawneh

Post-post modernity. It’s rare that (good) fictional cinema keeps pace with organically reflecting the immediate flux of the times. There tends to be a five-ten-year period following the advent of widely blooming new social movements, world events or technological advancements before the movies can catch up in a way that doesn’t make us unintentionally laugh or cringe. It’s like how for the longest time filmmakers couldn’t figure out how to display text messaging conversations on screen in a way that wasn’t wonky or awkward. They eventually figured it out it just took a while. Bonello, with The Beast, has achieved the first film I’ve seen that gave me the feeling of how absurdly caustic, gleefully hateful our global cognitive dissonance has accelerated. A couple of my friends hated this, (including Dave, who’s states why above) and I totally see why they would. It’s a deeply unpleasant film, by design, uncompromising in its densely layered dream logic, or nightmare logic, on its own plane of coherence. It jeers at you, with disregard for whether you’re able to meet it on its own terms. I can’t imagine this remotely working at all if not for Léa Seydoux, our current greatest living actor. Her ability of convincing expression among conflicting tonalities feels like cheating, as in it shouldn’t work but does; see also: Bruno Dumont’s own contorted interpretation of the present, the excellent France (2021). It’s also funny that Dave mentions Assayas in his capsule—2002’s Demonlover came to mind while watching this.

I spent a lot of time during the initial pandemic years shuddering at the idea of “COVID cinema” because I couldn’t think of something that sounded less appealing*, but understood it was an inevitability; one of the miracles of film is the medium’s capacity to reconcile an audience with ugly societal ills we prefer to scrub our minds of. If covid repulses as an area to address in a movie, imagine the optic disgust around selling an exploration of incel culture in a way that’s intelligent or artful. Bonello pulls this off in ways I cannot articulate off an initial viewing. My overwhelming enthusiasm for this comes purely from instinct, from the insanely rare occurrence of a movie making me reevaluate everything, like a lightbulb suddenly switching on.

*There are recent examples of good COVID movies such as Miguel Gomes & Maureen Fazendeiro’s The Tsugua Diaries (2021), Radu Jude’s Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn (2021) and Bonello’s previous film, Coma (2022).

Chikcen for Linda! [Linda veut du poulet!] (2023) — Sébastien Laudenbach, Chiara Malta

By Dave Gomshay

Outstanding. Genius animation, simple but looks like nothing I'd ever seen before. Story opens with a gut-wrenching tragedy. Proceeds to become one of the funniest, most exuberant films I've seen in a while. Non-stop inventiveness, wonderfully detailed characters and relationships. And songs! No one told me there'd be hilarious, perceptive songs! I loved it, hope it gets more attention and not written off as just a goofy movie for kids.

Guardians of the Formula [Cuvari formule] (2023) — Dragan Bjelogrlić

by Nazeeh Alghazawneh

A competently made, Eastern-European period piece that plays with familiar historical narrative tropes in neat, linear fashion. You know the beats, Cold War era, frantic scientists with conflicting ideologies, must work together to clandestinely cure an unprecedented disease, and make history. It’s very watchable, but I couldn’t help but be reminded of other recent examples that I found more memorable, Nolan’s Oppenheimer, HBO’s Chernobyl. Not bad by any means, but a film I probably won’t think about ever again.

Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell [bên trong vo kén vàng] (2023) — Pham Thien An

By Dave Gomshay

Sometimes a movie designated as "slow cinema" feels like it flies by, regardless of how long it actually is. This one felt much longer than its three-hour runtime. On the one hand, I'm delighted by the audacity of the director completely immersed in his mission here, somehow procuring a sold-out crowd for this screening and insisting they adjust to his rhythm and his mind and his terms. There are some incredibly mesmerizing passages in this. But I felt pretty blank through most of it, even when I saw things happening on screen that I knew were supposed to be momentous and sublime. I'll take away good impressions of various scenes and how they were filmed. The lead actor actually gave a pretty great performance. And what the hell, why am I seeing so many reviews online complaining about the Christian content, as if they were tricked into watching some sort of religious propaganda or something?

by Nazeeh Alghazawneh

Perhaps too languid for its own good, but it’s an indulgence I find to be forgivable for a feature debut. My good friend Dave Gomshay expressed that he felt the film felt longer than its 179-minute runtime, but it didn’t feel as severe to me; yes it was too long but I guess it didn’t bother me as much. definitely more positive than negative on it overall, there’s plenty of strong material here. It’s always pleasant to look at, with ethereal, painterly compositions of Vietnam. There’s a vastness to the frame, all this negative space, with the characters hanging onto the fringe, inundated by the weight of their circumstances, and the theological implications of them. Christianity’s role, specifically Catholicism, in these peoples’ lives is a present factor but deeper than that, the film explores other dueling kinds of doctrines just as pervasive, capitalism as an equal, driving form of worship. As someone who always admires a well-acted child performance, The relationship between the main character and his nephew is also very sweet, and palpable.

Mambar Pierrette (2023) — Rosine Mbakam

by Nazeeh Alghazawneh

I loved this Cameroonian narrative executed with lucid, documentarian aesthetics. Mambar Pierrette is a highly skilled dressmaker trying to survive in the city of Douala, against archaic, patriarchal structures and a sort of cosmic misfortune. Rosine Mbakam blends her documentary background with her first fictional work so fluidly, the marriage more closely resembling docu-fiction. The suspension of disbelief usually attached with narrative coherence is nullified by Mbakam’s loose, handheld camera closely hanging around, following Mambar, as she interacts with various members of her community. Community as a mutual source of strength and support, specifically among the women around Mambar, bares the richness of her interiority and the film’s milieu. It’s bleak, but not miserable, never positioning Mambar as a victim, despite her enormous hardships.

The Old Oak (2023) — Ken Loach

By Dave Gomshay

Heavy-handed doesn't begin to describe this. I've seen plenty of Ken Loach movies (LADYBIRD, LADYBIRD is an all-timer), but this one just kept hitting familiar Loachian notes, with some not-great actors and awkward dialogue needlessly milking sentimentality. We get it, Ken! I'm onboard with the politics, but the storytelling is clumsy and corny.

Only the River Flows [he bian de cuo wu] (2023) — Wei Shujun

by Nazeeh Alghazawneh

Mildly compelling, but ultimately unremarkable, standard crime procedural of a stoic cop who internalizes the bleakness around him. The vicious cycle of obsessing over a murder case to avoid your marital problems. The heavy dread of Zhu Yilong’s fine performance is probably the only reason the movie works at all.

A Ravaging Wind [El viento que arrasa] (2023) — Paula Hernández

by Nazeeh Alghazawneh

A melancholic film told through the POV of Leni, a young girl on the cusp of womanhood, as she travels across the Argentinean countryside with her reverend father on missionary work. Her father is pathological in his practice, disposing him to that classic religious fallacy of megalomania where you believe you are a literal vessel for God’s Word. The cinematography is stunning, lending itself to this transcendental grandeur through wide, maximalist shots of the things that emphasize our insignificance to an infinite universe we can only perceive in abstraction—landscapes, the elements, the sun and the moon. The pacing is brooding, amorphous, concerned less with resolution and more with wading through the characters’ existential flux. There’s a languorous quality I enjoy, unique to Argentinean films—I’m thinking of the work of Lucretia Martel, Lisandro Alonso, Laura Citarella—that is present here. It’s not the same caliber as those filmmakers, but it’s in that register for sure, and very promising.

Sing Sing (2023) — Greg Kwedar

by Nazeeh Alghazawneh

A by-the-numbers inspirational prison tale of inmates who use theater as a positive outlet for their incarceration. The two lead performances by Colman Domingo and Clarence Maclin, who plays himself, in a film based on true events, are the highlight of the ensemble. Domingo is naturally charming in everything he’s in so it’s a testament to Maclin’s electric screen presence that he shines opposite a professional. I would love to see him in future film work. It’s a good-looking film, showcasing that nice shimmer that 16mm gives you. Even though many of the actual inmates play themselves here, and perform well, I do wonder how this story would translate in documentary form, as I found the real-life footage shown at the end the most captivating.

Solids by the Seashore (2023) — Patiparn Boontarig

by Nazeeh Alghazawneh

We are an extension of the earth, our bodily composition merely rearranged from the same elements we mistakenly think we can control. I really loved this. A gentle, sensual unfurling of the intersection among culture, religion, sexuality and environmentalism in a Thai context. It’s enormously tricky to convey Muslim stories that explore life traditionally thought to be “outside the faith” with sensitivity and nuance. There’s usually this inclination to use Islam as a justification to apply a finite, black-and-white world view to an existence that is anything but, regardless of faith. It’s painfully lazy and boring. Instead, Patiparn Boontarig deftly weaves God-like, bird’s-eye-view compositions, a serene, wonky electronic score and the sweet affair of its women protagonists to the circadian rhythm of the omniscient ocean waves around them.

SWAMP DOGG GETS HIS POOL PAINTED (2023) — Ryan Olson, Isaac Gale

By Dave Gomshay

Generally not a fan of music docs—the droning talking heads, the tedious rise/fall/redemption arc...which happily this doc largely avoided. Swamp Dogg and his crew all came across as genuinely sweet and positive creators, doing good work in this stupid world. Next to nil cynicism to be found. Pretty infectious spirit on the screen and in the audience, filled as it was with friends and fans of the hometown filmmakers.

Tiger Stripes (2023) — Amanda Nell Eu

By Dave Gomshay

Director Amanda Nell Eu mischievously blends Julia Ducournau with Lukas Moodysson in this Malaysian pre-teen body horror joint. The three young leads in this are incredible. Zafreen Zairizal is 12-year-old Zaffan, who's going through changes. Her face contorts into feral snarls and paralyzing glares, her body crouches and coils and flails. At the other end of the spectrum but, just as compelling, Deena Ezral's Farah says it all with just her subtle scowls and twitching brows. The mononymous Piqa straddles the middle as Mariam, torn between her two suddenly warring friends. Refreshingly old school effects and make-up enhance the proceedings, nothing fancy but it works. The final shot of Zaffan fully immersed in her new self puts a triumphant, satisfying stamp on it all.

Tomorrow is a Long Time [Míng tian bi zuo tian chang jiu] (2023) — Zhi Wei Jow

by Nazeeh Alghazawneh

A two-hander that can’t tell its right from its left, leaving the film exploring its aspects that are least compelling. A maladjusted, recently widowed father trying to raise his son serves as the first half’s orientation, only to be abandoned for a complete, bifurcated shift to an exploration of the teenage boy’s budding adolescence. Unfortunately It’s the father’s static grief anchoring the dramatic resonance, and once he exits, there’s not much else to chew on; the actor playing the son cannot carry the narrative independently.

Voy! Voy! Voy! (2023) — Omar Hilal

by Nazeeh Alghazawneh

There is a very specific facial expression that’s captured in Voy! Voy! Voy!, one that I could only describe as the “dumb Arab guy face”. It’s an expression I’ve seen my whole life (that I myself have undoubtedly made), that is born from the lifelong infantilization of a son by his mother. It’s a specific kind of coddling that is recognized among the Arab/Muslim world, where sons are granted the freedom to be as flawed, as irresponsible, as cavalier as they’d like. The arrested development that leads to makes for rich, comedic fodder in skewering man-children. Omar Hilal’s acidic, Egyptian tale of a screw-ball degenerate, along with the help of his equally good-for-nothing friends, pretending to be blind so he can play on an all-blind soccer team hits incredibly hard because its self-aware ethos of the “dumb arab guy face” is understood so well. One of the film’s best jokes is Hassan, the protagonist, going through all this trouble in an effort to escape Egypt, for Poland, arguably the Egpyt of Europe.

about the contributors ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭

Dave Gomshay eats movies for breakfast. He has been a volunteer at the Trylon Cinema for over 10 years. He is part of the Archives on Screen team, which brings rare, unseen archival films from around the globe to movie screens in the Twin Cities. In the past, he has volunteered for the Minneapolis/St. Paul International Film Festival as a submission reviewer. He enjoys all kinds of films, whether they be artsy, fartsy, or even artsy-fartsy.

Natalie Marlin is a freelance writer based in Minneapolis. She is the author of the forthcoming book Noise Music, part of Genre: A 33 1/3 Series, and has work published in Bright Wall/ Dark Room, Reverse Shot, and Little White Lies. She likes Technicolor, DV cinematography, and the films of Takashi Miike.

![MSPIFF43: Occultist Revenge, Satirical Body Horror, Feminist Archives, Absurdist Dystopia, and Surreal Duration [Dispatch #2]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/61c8155b43afc26b6ecbd8b6/1714848446780-C3F9Z5P8QTCD396P2U0Q/copa+71+2023.jpeg)