MSPIFF43: Occultist Revenge, Satirical Body Horror, Feminist Archives, Absurdist Dystopia, and Surreal Duration [Dispatch #2]

Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell

by Maggie Hennefeld (University of Minnesota)

April was a month of bountiful cinematic offerings in the Twin Cities. L.A. Rebellion filmmaker Zeinabu Irene Davis visited the Walker Cinema to present a rare 16mm screening of her masterpiece Compensation (1999), which is finally being restored by Janus/Criterion and will have a theatrical release this fall 25 years after its festival premieres in Atlanta and Toronto in 1999. Mizna launched its new “Insurgent Transmissions” series with a packed screening of Annemarie Jacir’s humorously heartwarming Palestinian road movie, Wajib (2017), in the glorious Bryant Lake Bowl Theater. Alfred Hitchcock and Arnold Schwarzenegger vied for repertory eyeballs at the Trylon Cinema. Last but not least, the 43rd Annual Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival! This year’s line-up included over 200 screenings—not to mention industry panels, director interviews, special events, and galas galore. I personally struggle to clear my end-of-semester schedule for those 2 weeks every April, when I would love nothing more than to dive headfirst into the treasures of MSPIFF! This year, I managed to attend 5 screenings. Here are my brief thoughts—with thanks to Nazeeh Alghazawneh for inviting me to share.

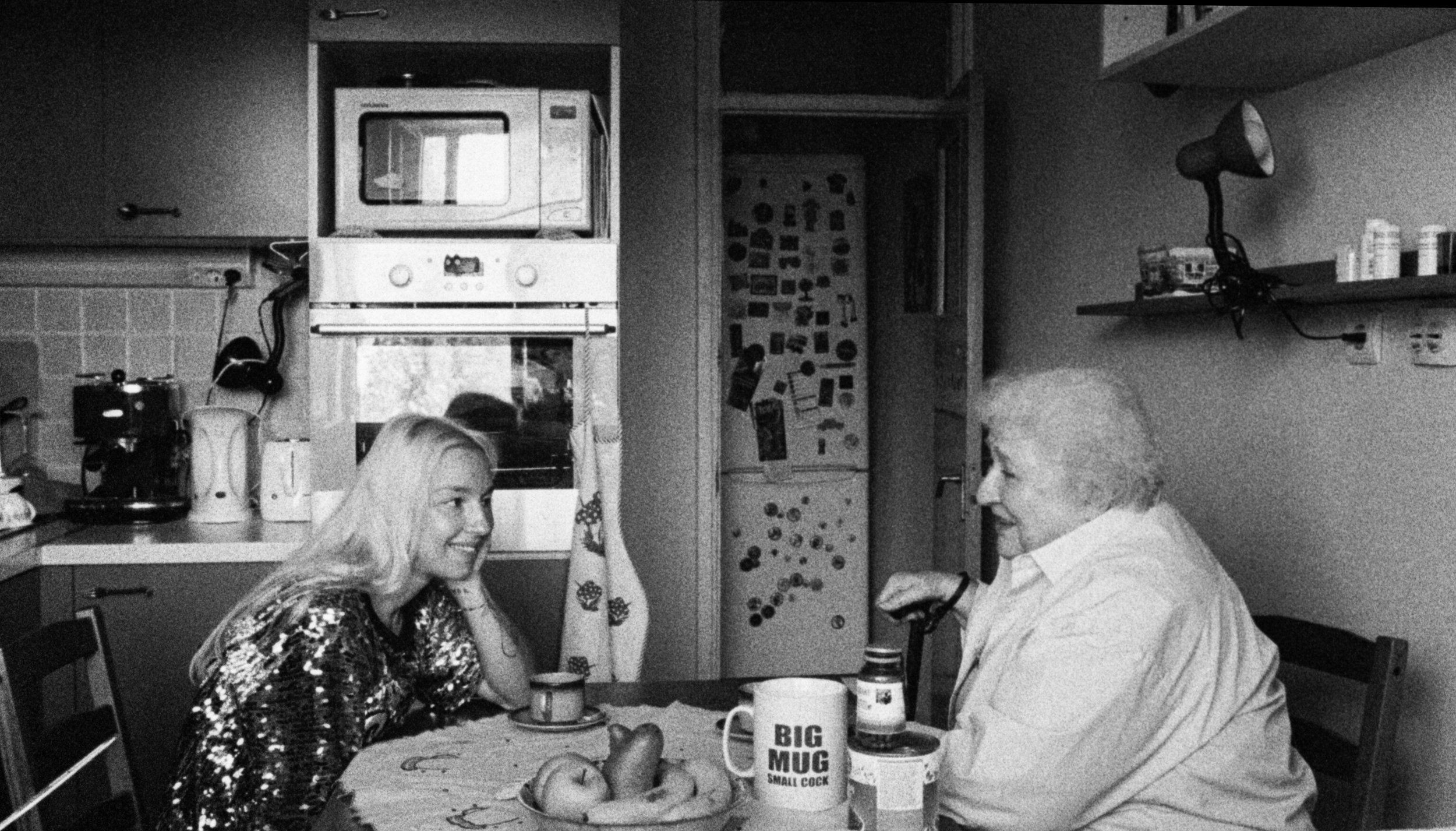

Copa 71 (2023) — James Erskine, Rachel Ramsay

The only documentary feature I managed to catch in the festival—which boasted regional premieres of new docs such as Porcelain War, Sugarcane, and Daughters, along with biopics on Luther Vandross, Anita Pallenberg, and John Galliano—this one felt especially timely. A conventional talking-head exposé, Copa 71 seamlessly interweaves extensive archival footage of the 1971 Women’s Soccer World Cup, whose explosive international popularity provoked FIFA to suppress women’s participation in the sport and censor public memory of these events in Mexico City and Guadalajara from the history of women’s professional athletics. Co-produced by Venus and Serena Williams, Copa 71 sets the record straight.

Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World [Nu astepta prea mult de la sfârsitul lumii] (2023) — Radu Jude

I enjoyed this film as much as I felt profoundly irritated by it. Romanian rabble-rouser Radu Jude’s provocauteurism is often a self-congratulatory Godard quote (or Méliès wink) away from overshadowing the substance of his film’s satirical critique, which is otherwise on point. To paraphrase the film’s thesis, nothing is real and the material consequences are brutal. Media surfaces—from green screens to TikTok filters to Zoom virtual backgrounds—add an absurdist edge to the freewheeling pastiche whereby workers are homicidally exploited, violent misogyny runs rampant, and corporate elites commit ritual cannibalism as a staple of their plant-based diet.

Evil Does Not Exist [Aku wa sonzai shinai] (2023) — Ryûsuke Hamaguchi

I’ve been a big fan of Hamaguchi’s fluid cinematography and slow-burn character studies since marathoning his 5+ hour opus (perversely titled) Happy Hour (2015) during the long months of pandemic lockdown. His films encourage a patient gaze—allegory escalates across episodic encounters in ordinary spaces of isolation and movement: on the bus, in a corporate cubicle, driving a car, or protesting a “glamping” development. Despite its slightly shorter running time than The Sound of Waves (2012) or Drive My Car (2021), Evil Does Not Exist delights in the utter beauty of evocative tedium in a world addicted to relentless novelty, extraction, and spectacle. The film’s tantalizing title “evil does not exist”—an alleged Albert Einstein quote with Arendtian vibes—recalls Freud’s definition of negation: no means yes, at least in the analytic context of unconscious repression. In other words, evil does not exist. Then again, maybe it’s the absent spectator who does not, as we project ourselves into ambiguous fantasy worlds while the planet implodes on the altar of new “glamping” developments.

Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell [Bên trong vo kén vàng] (2023) — Thien An Pham

“Slow cinema” at its most resplendent. A road movie about ghosts—present and absent—this film has a visceral texture that you learn to inhabit over the course of several hours, from the sensation of a cellphone vibrating in a massage parlor to a jerky motorbike tracking shot and through a series of surreal fantasies and vivid nightmares. I am still jostling some of the film’s images out of my body.

Working Class Goes to Hell [PRadnicka klasa ide u pakao] (2023) — Mladen Djordjevic

Keeping apace with my appetite for class revenge body horror, it was a no-brainer to stay out after my friend’s 39th birthday party for a late-night screening of this diabolical satire. Crudely summarized, the Balkan proletariat embraces the paganist occult after a factory fire leaves them destitute and bereaved. Radu Jude’s revisionist take on the Lumière Brothers’ early actuality footage of Workers Leaving the Factory (1895) in Do Not Expect Too Much… called this film again to mind. Where else do workers go after leaving the factory, if not inevitably back to hell? Except Đorđević’s version of hell is a feast for the bodily lower stratum! The bloody climax feels well earned: the oppressed people rise up and demand carnal liberation from their political wounds, festering emotions, and violated libidos. Though inconsistently weird and unevenly paced, there was nowhere else I’d rather be at midnight on a Saturday.

*An afterthought on methodology

Of the 200+ films in the festival, why did I choose these five, and how might their totality offer us a snapshot of this current moment in international arthouse cinema? Class revenge, apocalyptic satire, absurdist malaise (of somehow continuing on despite living after “the end”...), and slow-burn durational possibility are a few of the core themes that have struck me and stayed with me in retrospect. When can cinema open up gateways onto alternative realms and unrealized historical potentials—as genocides unfold with impunity, protests rage on college campuses across the US, the planet floods and burns, and class immiseration fuels the flame of resurgent authoritarianism? What (if anything) does cinema have to say in response? According to my (albeit fragmented) experience of MSPIFF, moving images still provide vital lifelines for a re-enchantment of the broken present: uncovering lost archives, releasing suppressed sensations, or simply remembering when, at last, it is time to say enough is ENOUGH!!!

about the contributors ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭ ٭

Maggie Hennefeld is Professor of Cultural Studies and Comparative Literature at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. She is the author of Death by Laughter: Female Hysteria and Early Cinema (Columbia UP, 2024) and Specters of Slapstick and Silent Film Comediennes (Columbia UP, 2018). She is a curator of the 4-disc DVD/Blu-ray collection Cinema's First Nasty Women (Kino Lorber, 2022) and co-director of Archives on Screen, Twin Cities.

![MSPIFF43: Occultist Revenge, Satirical Body Horror, Feminist Archives, Absurdist Dystopia, and Surreal Duration [Dispatch #2]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/61c8155b43afc26b6ecbd8b6/1714848446780-C3F9Z5P8QTCD396P2U0Q/copa+71+2023.jpeg)